Estate Planning for Families Who Have a Loved One with Down Syndrome

Hal Wright is the author of the must-read book ‘The Complete Guide to Creating A Special Needs Life Plan.’ After 27 years in finance, Hal became a beloved Certified Financial Planner specializing in planning for those with special needs. He is now retired but active on the speaking circuit.

From Down Syndrome World Issue 1, 2023

This is for families who have a loved one with Down syndrome— a child, a brother, a sister, a grandchild or perhaps a friend. I will primarily address the social aspects of estate planning without going into the legal or financial aspects, except that I will briefly address the role of a special needs trust in an estate plan. I also want to emphasize the importance of end-of-life care planning for a person with Down syndrome.

I have a daughter with Down syndrome in her mid-thirties. She has lived in her own apartment for ten years, independently with supports. A “child” in this article doesn’t mean someone under age 18. My daughter will be my child no matter how old she is.

ESTATE PLANNING 101

Estate planning is for anyone who has something valuable to leave to a loved one. By something valuable I mean real estate such as a house, financial assets such as retirement savings, death benefits from a life insurance policy, collectibles such as art, and so forth. Basically, anything that can be titled, valued, sold, or cashed in should be considered a potential element of an estate. Obviously wealthier families who own valuable property, a business or who

have substantial wealth will have complicated estate plans. However, even a family that has nothing to leave but love should consider how that love will be expressed and passed on. For them, a life plan for their child is a truly valuable legacy.

All parents should have a life plan for a child with special needs that describes the parents’ wishes for the child and the child’s wishes for themselves. The plan includes what is necessary to make it possible, that is, the resources and supports. All financial and legal plans, including estate plans, start with a life plan. A family’s financial plan and the parents’ retirement and estate plans must consider the cost of the child’s lifetime support and how to provide for it. There are five things you do to create a sustainable plan:

1. Develop a life plan and update it periodically for changes in circumstances. Pay special attention to major life transitions like aging out of school or the death of a parent.

2. Establish a circle of support to manage the life plan through all the years of the child’s life. This is especially important should the child outlive her parents.

3. Teach the life skills for community participation and maximum independence.

4. Write a letter of intent (LOI) to document the life plan including the arrangements you have made for care and support after you pass away. The LOI guides the people in the circle of support.

5. Decide on the forms of protection and oversight that the child will require when you’re no longer able to care for him yourself. This could be a court-appointed guardian whom you choose, personal advocates, agents holding powers of attorney and fiduciaries for managing money.

ACCOUNT FOR UNEXPECTED CIRCUMSTANCES

Too often inadequate consideration is given to how a plan evolves as the child ages. There are two important considerations to plan for.

First, parents should consider the possibility that their child could outlive them, especially if one parent dies or both die prematurely. Adequate life insurance is almost always a “must have” to the extent affordable. People with Down syndrome have shorter life spans than the wider population. Currently their life expectancy is around sixty years of age . (A life expectancy means half of the people will die earlier and half will die later than that age.) However, women who are over thirty-five years old have a higher chance of having a baby with Down syndrome than those who are under thirty-five. Thus, it is quite possible that a baby will outlive middle-aged parents if the child remains healthy throughout life. My daughter will likely outlive me, perhaps by fifteen years. She may outlive my spouse, Eleanor, who could well live into her nineties. However, Eleanor will likely experience the diminishments of aging (perhaps dementia) at an earlier age at the same time our daughter is needing greater care.

The second consideration, and the most tragic, is Alzheimer’s disease, the symptoms of which begin to appear in many adults with Down syndrome in their mid-fifties. Over fifty percent of people with Down syndrome will show symptoms by age 55. Therefore, and I cannot stress this enough, planning for the end-of-life care for someone with Down syndrome due to early onset dementia is something you must do. If your child is an adult, you cannot count on a medical miracle that will lift this scourge from our loved ones. While organizations like the Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome and the Global Down Syndrome Foundation are making progress, biologists and medical researchers have searched unsuccessfully for a cure for AIDS for over 40 years. Same with cancer.

It is quite possible that an individual who shows symptoms at age 55 could live for another six or seven years. In that span he may progress from care in an assisted living facility to eventually moving into a cognitive custodial care or skilled nursing facility. The problem is how to pay for the cost. Quality care is very expensive. Most parents plan, or perhaps only hope, they will take care of their child in their old age. This can become seriously unrealistic as they age and experience physical or cognitive decline or a serious disease themselves.

WHAT IS THE COST OF LONG-TERM CARE?

How expensive is the cost of care in a facility? In Denver, Colorado, the average cost of a private room in an assisted living facility in 2023 will likely range from $70,000 to $75,000 per year. (Costs as well as the quality of care vary widely.) Cognitive custodial care for dementia is around $90,000 annually. A private room in a skilled nursing facility is in the range of $130,000 a year. This presents a serious challenge for most families planning for their child’s end-of-life care. How can people pay such huge expenses over a five to seven year period?

Medicare does not cover the cost of long term care in a facility. Medicare is the federal health insurance program for people who are 65 or older, who have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or end stage kidney failure, or who have received Social Security Disability benefits for twenty-four consecutive months.

What then, are the options?

Wealthy families will pay for the highest quality care. About ten percent of the American population are affluent enough to do so.

About twenty-five percent of the aging population has long term care insurance (LTCI) to cover the cost. Not surprisingly, it is impossible to get LTCI for a child with a disability.

Medicaid is a joint federal and state program that provides health coverage to people with low income. Medicaid pays about two-thirds of long-term care costs in this country because people either haven’t planned for it, they never had the financial means to buy insurance (it’s expensive), or they haven’t been able to save enough to pay for the care themselves. Anyone who has ever had a loved one, such as a parent, in a Medicaid facility will not want their child to end their lives in one if they can help it because of the problems with quality of care and concerns about abuse and neglect.

The considerations just described are why parents who have a child with special needs should be very serious about estate planning. An essential element of their estate plan will include an adequately funded trust to ensure the child’s (the beneficiary’s) lifetime financial support. Wealthy families will usually create a disability trust. Less affluent families will create a special needs trust which allows parents to leave money for their child’s support without affecting eligibility for means-tested government assistance such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Medicaid, and the Home and Community Based Services programs for persons with disabilities (HCBS, also called Medicaid-waiver). The two most common ways for funding a trust are regular contributions to a trust during life and life insurance. Life insurance is the most common way trusts are funded. Many use both. I use both.

Pre-funding end-of-life care for a child with Down syndrome will be, or certainly should be, a significant consideration in funding a trust. The costs of care will likely be in the range of a few to several hundred thousand dollars depending on when and how you fund the trust. This is why adequate life insurance is a must for most families.

Special needs planning includes a wide range of sophisticated and complex issues. Parents can and should do life planning themselves with assistance in areas such as social services and education. Most families will need professional advice for legal and financial planning. It is straight forward to find attorneys to draft legal documents such as personal wills and trusts. These attorneys practice in the domains of Elder Law and Trusts and Estates Law. It is harder to find financial planners who are knowledgeable, experienced, and ethical. I strongly recommend Certified Financial Planners or CFPs. I encourage you to work with a financial planner before you go to a life insurance agent. You should know what you need, not what someone wants to sell you.

WHERE DO YOU GO FROM HERE?

I have hit a few major considerations in special needs planning, but this article only scratches the surface. When I give presentations to parents and families, I leave them with: “Where do you go from here?” So I leave you with this. I have written a book on the subject: The Complete Guide to Creating a Special Needs Life Plan. Published in 2013, it explains how to create a comprehensive plan integrating the life, resource, financial and legal plans into a practical plan of action. When it was published, the Library Journal, the journal for professional librarians, gave it a red star review (meaning recommended for library acquisition) with the verdict: “Essential.” It still sells on Amazon. It is 360 pages in length with four, twenty-five-page case studies to show readers what a realistic plan looks like.

Although ten years old, it remains relevant today. If I were to update for a second edition, I would add a chapter titled: “A Home of Her Own: Supported Independence.” I passionately believe that supported independence for most adults with Down syndrome is a realistic goal with adequate planning, resources (including financial), and a good life plan.

I’ll close with a thought for those who are financially well-off enough to leave a substantial legacy. Most people think first about those they love – their spouse, their children, their grandchildren or a loved one like a brother or sister. However, some may want to consider a legacy to a charity or institution that has made a meaningful contribution to your child with Down syndrome’s well-being.

My daughter is in a race against time, a race between the clock as she ages and the medical professionals searching for a way to block the amyloid-β protein path, the significant contributor to the development of Alzheimer’s Disease.

I put this forth for my daughter’s sake and perhaps yours. Please consider in your estate planning, if you have the means to do so, a contribution to fund the research to stop this vicious disease and lift this scourge from our children.

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant!

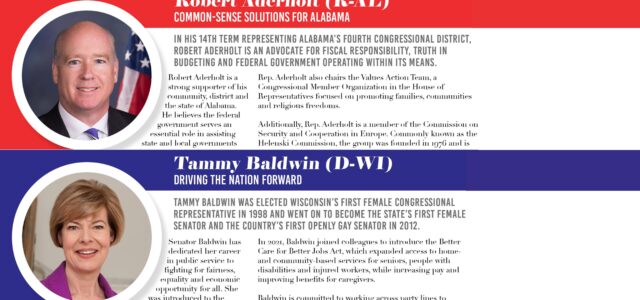

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant! Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.

Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.