What Parents Need to Know About IEPs

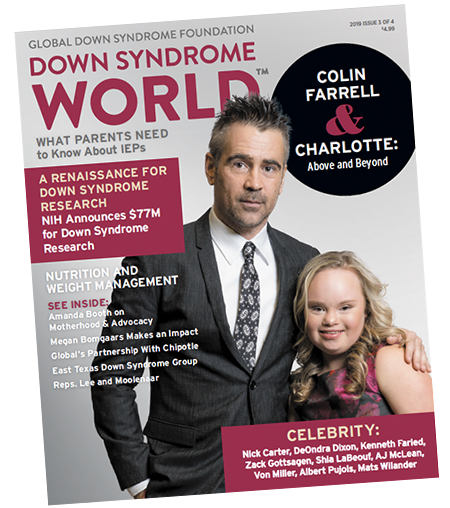

From Down Syndrome WorldTM 2019 Issue 3 of 4

Individualized education programs are detailed learning plans for students K-12 with intellectual and developmental disabilities enrolled in public school. The process of obtaining, developing, and implementing an IEP for your child can seem overwhelming. Knowing what to expect and planning can help streamline the process.

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door!

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door! UNDER THE INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES EDUCATION ACT (IDEA), students with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) enrolled in public school may be eligible to receive free, customized learning plans for their education. Individualized education programs (IEPs) are legally binding plans developed by a team of parents/guardians, teachers, and any other stakeholders that set the course for students with special needs. To obtain an IEP, a child must be enrolled in public school, must be between 3 and 21 years old, have one of 13 intellectual or developmental disabilities, and take eligibility tests administered by the public-school system.

WHAT IS AN IEP?

“An IEP outlines when and where a student will receive instruction, how the student is going to access the curriculum and what curriculum he or she will be accessing … what services will be provided, such as speech-language, occupational, or physical therapy, and who will be providing those services,” says Jennifer Harris, M.S.E., Education Specialist at the Anna and John J. Sie Center for Down Syndrome at Children’s Hospital Colorado, an affiliate of the Global Down Syndrome Foundation.

The Sie Center was the first to embed a full -time education specialist into a Down syndrome medical center in the United States. Harris joined the Sie Center in 2017 and works closely with patients, parents, and teachers to support the education of individuals with Down syndrome. She also works alongside Lina Patel, Ph.D., Director of Psychology at the Sie Center, to help patients navigate the barriers to their education by looking at their unique behavioral profile.

IDEA states that children who are differently-abled should receive a “free, appropriate, public education” in the “least restrictive environment” possible. Children who attend public schools, including charter schools, are eligible for IEPs, but private schools are not required to provide them.

Before a child reaches age 3, families may be eligible through Early Intervention, to receive an individual family service plan (IFSP). This document outlines services young children will receive to support their development prior to entering a public education system — either in pre-school or at home. The team that creates an IFSP includes parents/guardians, professionals such preschool teachers, therapists, any outside advocate or specialist requested by the family, and a service coordinator from the state to help determine needs and implement the plan. When children turn 3, they may transition to an IEP from their IFSP, however you do not need to have an IFSP to apply for an IEP.

EVALUATION TESTS

To start the process of obtaining an IEP, parents/guardians can ask the school district to initiate the evaluation process. The district may also ask the parents for consent to initiate if they have concerns as well. This will begin the assessment process. These assessments involve various tests to determine the child’s specific needs and the most appropriate accommodations for their learning.

Qualification is also based, in part, on whether the condition affects a specific aspect of a child’s learning abilities, such as oral expression, comprehension, or reading, writing, or math skills. Through a variety of tests, they will measure a child’s health, vision, hearing, social and emotional development, motor skills, general intelligence, academic skills, and communication

ability. When the evaluation is finished, the statistical results are presented in a report to all parties involved.

“Results of some of these tests can, potentially, be jarring to parents. No parent wants to read or hear that his or her child scored in a low percentile or significantly below average in certain areas. It is important to understand that this is only a small, fraction of the process,” Harris says. “Testing is fundamental to the process in order to understand the need for services.”

“No one test can be used and no one person can identify a child as having a disability and needing special education, so a variety of assessment tools and strategies must be used to collect relevant functional, developmental, and academic information,” explains Melody Musgrove, Ed.D., Co-Director of the Graduate Center for Early Learning and Associate Professor of Special Education at the University of Mississippi.

There are cases where parents/guardians oppose an IQ test or some standardized testing they feel is not reflective of their child’s ability. While this can hold up the IEP process, it is within a parents’/guardians’ right to not agree with certain testing, and it’s within their right to reject in part or in full the IEP the school presents. There are cases where parents/guardians sue the school to get the services they need, but hopefully legal recourse can be avoided if the family, school, and teachers are all on the same page. There are several avenues that parents and school teams can take to help come to a collaborative middle ground. Many states offer IEP facilitators and options to obtain an educational advocate. These professionals are not attorneys, but they are trained in disability law and can provide an unbiased, fact-based opinion that keeps your child’s educational rights intact.

Although these tests are mandatory, sometimes the methods are flexible and can include verbal and nonverbal formats. Harris encourages families and school teams to look at a variety of cognitive tests to select the most appropriate assessments for the individual child, providing an adequate representation of that child’s skills, capabilities, and needs.

“Your child is still your amazing child, and assessments aren’t going to capture all of the things he or she can do or all the beautiful things that make your kid who he or she is,” she points out. “Look for relative strengths. For example, even if your child is scoring ‘extremely low’ in several categories but maybe just ‘low’ in another area, look at that as a relative strength. Figure out how to draw upon that to support your child’s learning.”

A multidisciplinary team (which simply means professionals from different disciplines, such as special education teachers, psychologists, regular education teachers, and speech language therapists, within the district as well as parents) will determine whether your child meets IDEA’s criteria for special education. If the team deems special education appropriate, your child will be reevaluated every three years.

Reevaluation can take place earlier, if a change in medical condition occurs, your child isn’t making progress in school, or the team suspects that your child no longer requires services.

YOUR IEP MEETING

The First Meeting

Within 30 days of determination of eligibility, the multidisciplinary team is required to develop the IEP in collaboration with the parents and to hold a meeting to review the document.

During the meeting, you’ll review the IEP section by section, including your child’s present level of academic performance, goals for the academic year, how you’ll be informed of progress, special education services the school will provide, accommodations your child will receive, and how and to what degree your child will participate in general education activities.

The school district is responsible for scheduling the meeting, inviting the parents/guardians, and ensuring the proposed time is convenient for them. However, each state has its own timetable for providing notice of a meeting. Parents are not required to attend the meeting but must provide written permission for services to begin. IDEA specifies that your child’s IEP team must consist of a special education teacher, general education teacher, school district representative or administrator who is knowledgeable about general and special education, and an individual who can explain the results of the comprehensive evaluation, such as a school psychologist. Other professionals, such as a speech-language pathologist, may be present.

Be Prepared

At least one week before the meeting, Harris recommends parents request, in writing, a copy of the assessment, the evaluation report, and any other documentation the IEP team will discuss.

Make sure you have time to review the IEP document and write down any questions you have. Questions may include what a word or acronym means or why an accommodation that you believe is important is or isn’t listed. While you prepare, Dr. Musgrove recommends turning to your most valuable resource for information: your child. Ask for his or her thoughts about how things are going at school. Write down any questions you have and your vision for your child’s education. Gather supporting documents, such as medical notes or previous schoolwork that you wish to review with the team. Create a fillable sheet to write down agreed-upon goals and supportive services during the meeting. If you wish, invite a friend, family member, or another individual who knows y our child to attend for support.

WHAT PARENTS NEED TO KNOW

Beware of jargon — if you don’t understand a term, ask the team to explain it in clear, concise language. Ensure the language in the IEP is unambiguous about the services to be provided, when they will begin and end, and your child’s goals.

“If parents don’t agree with the IEP, they need to say, ‘I no longer want this meeting to continue, I need to contact an educational advocate,’ and obtain an educational advocate to walk through next steps,” Harris advises.

Once parents and the school district agree to the IEP and services begin, communication is crucial. If you notice your child struggling in a certain area, notify his or her teacher right away instead of waiting until the next annual IEP review meeting.

IDEA requires an IEP review meeting at least once a year, but parents can request one at any time.

“Parents may find it helpful to have an IEP review meeting at the beginning and end of each academic year, as well as a midyear meeting to get a sense of their child’ s progress,” says Julie

Youssef, D.O., M.P.H., Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrician and Clinical Assistant Professor of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics at Stanford University School of Medicine.

“Starting at age 16, the child must be invited,” Dr. Musgrove says.

“I encourage parents to have their children attend IEP meetings much earlier — not necessarily the entire meeting — so they can learn to self-advocate.”

Most importantly, whether you’re new to the IEP process or have experience with it, trust your knowledge and judgment as a parent.

“A lot of parents may feel like they’re ill prepared [to navigate the IEP process], but they’re actually more prepared in ways that they may not immediately recognize,” Harris says. “No one knows their child better than parents … so they need to understand they’re pivotal players and hold information no one else will have. That’s the biggest mistake that parents make — not believing in themselves.”

Like this article? Join Global Down Syndrome Foundation’s Membership program today to receive 4 issues of the quarterly award-winning publication, plus access to 4 seasonal educational Webinar Series, and eligibility to apply for Global’s Employment and Educational Grants.

Register today at downsyndromeworld.org!

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant!

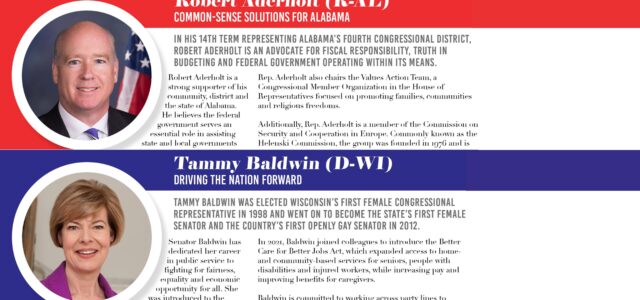

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant! Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.

Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.