Congenital Heart Defects and Down Syndrome:

What Parents Should Know

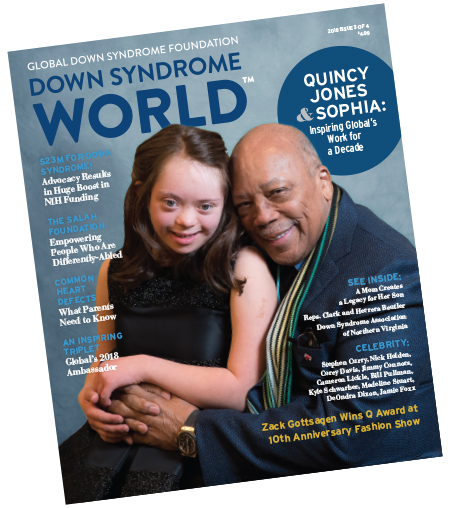

From Down Syndrome WorldTM Issue 3 2018

This rare disease is significantly more common in children with Down syndrome. Understanding symptoms and early detection could save a life.

CHILDREN WITH DOWN SYNDROME face a high rate of congenital heart defects (CHDs). In fact, about 50 percent of infants with Down syndrome have some form of heart condition, compared with approximately 1 percent of typical infants, although it is unclear why these conditions occur so frequently in children with Down syndrome.

Three of the most common heart conditions seen in children with Down syndrome are atrioventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, and tetralogy of Fallot.

ATRIOVENTRICULAR SEPTAL DEFECT (AVSD)

AVSD is the most frequently diagnosed congenital heart condition in children with Down syndrome. Various studies place the incidence rate between 30 and 47 percent of CHDs in children with Down syndrome, according to the book Advances in Research on Down Syndrome. A study from the International Journal of Cardiology estimates that AVSD accounts for just 7 percent of CHDs diagnosed in all children. AVSD is characterized by holes between either the upper or lower chambers of the heart, the atria and the ventricles, respectively.

In less severe cases, atrial septal defects (ASD) or ventricular septal defects (VSD) can occur separately. Both are caused by a “hole” in the wall the separates chambers of the heart. ASD affects the top two chambers, while VSD affects the two lower chambers.

AVSD can be diagnosed during pregnancy via ultrasound but may not be evident until a child is a few months to even a few years old. The condition almost always requires surgery, the type of which will vary depending on the kind and degree of AVSD. According to the Society for Thoracic Surgeons, which tracks heart surgery outcomes for all children, AVSD surgeries have a near-100 percent survival rate.

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door!

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door! PATENT DUCTUS ARTERIOSUS (PDA)

PDA accounts for 5 to 10 per cent of all CHDs in full -term infants and between 20 to 60 percent of CHDs in pre-term infants. For children with Down syndrome, it accounts for between 5 and 18 percent. This heart defect occurs when a channel called the ductus arteriosus that connects a fetus’ heart and lungs in utero does not close after birth. While it is frequently diagnosed after birth, not all children exhibit symptoms. When symptoms do exist, they include tiredness, sweating, quick or heavy breathing, disinterest in eating, and not gaining weight as expected in a growing child.

Doctors generally employ four treatments for PDA: watchful waiting to see if the ductus arteriosus closes on its own, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, surgery, or an outpatient procedure called a transcatheter device closure. Most children undergo catheterization, according to the American Heart Association (AHA), but treatments chosen often depend on a child’s age, degree of symptoms, and whether the particular PDA responds to medications. Children with PDAs have a higher rate of mortality than children whose PDAs are closed with treatment, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

TETRALOGY OF FALLOT

This heart defect is fairly rare in all children. The CDC estimates that it occurs in only 1 in 2,518 (0.04 percent) of all live births. However, it accounts for 2 to 6 percent of CHDs in infants with Down syndrome.

Infants with this heart defect have four different problems: a ventricular septal defect, a narrow or obstructed pulmonary valve, an enlarged aorta, and a thicker-than-normal right ventricle. The combination reduces blood oxygen levels in the rest of the body.

Tetralogy of Fallot, which is usually diagnosed after birth, requires an open-heart surgery called complete intracardiac repair. As children grow up, they may need additional surgery to widen or replace a pulmonary valve, which can leak and lead to a condition called pulmonary backflow.

Research suggests that 90 percent of all infants who have surgery for tetralogy of Fallot live into their 40s, according to the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, but these children often face heart problems, such as arrhythmia and coronary heart disease, later in life and require lifelong follow-up care with a cardiologist.

DETECTING PROBLEMS

Certain CHDs can be diagnosed during pregnancy by a pediatric cardiologist through noninvasive testing, such as ultrasound or fetal echocardiogram. Early diagnosis of cardiac issues is crucial to ensure prompt medical response after delivery and to improve an infant’s chances to survive and thrive. In addition, a pediatric cardiologist provides ongoing care throughout childhood.

Given the frequency of CHDs in babies with Down syndrome and the optimal one-year surgical window, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends every baby born with Down syndrome be evaluated by a pediatric cardiologist within one month of birth. This

recommendation includes children whose prenatal tests and general pediatrician found no trace of CHDs.

Whether a child with a CHD is diagnosed before or after birth, parents should, if possible, interview more than one pediatric cardiologist and cardiovascular surgeon, if necessary.

It’s also wise to ask an insurance provider about coverage for seeking a second opinion before parents decide on a care plan for their infant.

LONG-TERM PROGNOSIS

Until the early 1970s, providers were reluctant to perform heart surgery on children with Down syndrome who had CHDs, essentially predestining them to a lifetime of hear t problems. Research has since established that babies with Down syndrome fare very well after pediatric heart surgery, and delaying surgery beyond the first year of life increases the risk of problems in adulthood.

“It is much easier to find treatment for children with Down syndrome and heart defects than adults with the same condition,” says Dunbar Ivy, M.D., Professor of Pediatrics–Cardiology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Selby’s Chair in Pediatric Cardiology at Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Today, fewer providers avoid or delay surgeries to correct CHDs. Thanks to improvements in technology and greater knowledge of the conditions, doctors are better able to treat CHDs early, limiting their impact on a child’s life.

“If surgery is performed early, most children with Down syndrome and a hear t defect will do very well,” Dr. Ivy says.

As a child with Down syndrome and a CHD grows, he or she will need ongoing care from a cardiologist familiar with CHDs, Dr. Ivy added, whether or not the defect was repaired. Not all adult cardiologists are familiar with the unique needs of patients with congenital heart disease, but the Adult Congenital Heart Association provides an online directory at achaheart.org/your-heart/clinic directory that can serve as a starting point for research.

Like this article? Join Global Down Syndrome Foundation’s Membership program today to receive 4 issues of the quarterly award-winning publication, plus access to 4 seasonal educational Webinar Series, and eligibility to apply for Global’s Employment and Educational Grants.

Register today at downsyndromeworld.org!

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant!

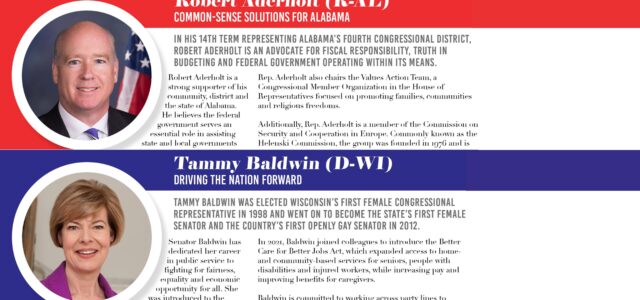

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant! Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.

Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.