Improving Quality of Life for Adults with Down Syndrome

A Lifetime Of Good Health Begins With Evidence-Based Guidelines

In the U.S., the life expectancy of an individual with Down syndrome has more than doubled in the last three decades, from 25 years in 1983 to 60 years today.

The reason for this increased lifespan is two-fold. First, the inhumane institutions where the overwhelming majority of people with Down syndrome were forced to live were dismantled in the 1980s and 1990s. This dismantling was a product of the human and civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s, which resulted in children with Down syndrome being raised in their homes and receiving education and medical care — basic rights they were deprived of in institutions.

Second, in the 1980s, there were considerable advancements in pediatric heart surgeries, as well as a legal battle that rightly ended with doctors being required to perform lifesaving procedures, including open-heart surgery, for children with Down syndrome.

Although people with Down syndrome are enjoying a significantly increased lifespan, their longevity is revealing some challenging age-related medical diagnoses. For example, it is estimated that approximately 70 percent of people with Down syndrome will develop Alzheimer’s disease. As they age, they are also at increased risk of many immune system disorders and obesity. Conversely, they are highly protected from several diseases, including most solid tumor cancers, such as breast cancer, as well as certain types of heart attacks and strokes. It is clear that people with Down syndrome have a different disease spectrum than typical people.

The American Academy of Pediatrics does an excellent job of periodically updating guidelines pediatricians should follow for their patients with Down syndrome. However, the last medical care guidelines for adults with Down syndrome were published in 2001. They provide many excellent insights and recommendations, but are in need of updates based on the increased lifespan of people with Down syndrome and advances in medical science.

In 2015, the Global Down Syndrome Foundation’s Task Force for Adults with Down Syndrome, a team of more than 60 self-advocates, their family members, and medical professionals, unanimously voted for Global to make updating medical care guidelines for adults with Down syndrome a priority.

“The primary purpose is to improve the physical and behavioral health of, and medical care for, people with Down syndrome. That’s absolutely why we’re doing this,” said Dennis McGuire, Ph.D., LCSW,

Senior Consultant at Global. He helped create the first adult medical care guidelines and is tasked with helping galvanize some of the leading medical professionals in adult care to establish new, comprehensive guidelines. “When we’re talking about health care and behavioral health, we’re talking about improving people’s quality of life. That’s our goal.”

EMPOWERING DOCTORS TO PROVIDE BETTER CARE

The new Medical Care Guidelines for Adults with Down Syndrome will provide medical professionals with updated information about adults with Down syndrome and a checklist of recommended screenings and tests that cater to the unique medical profile of this special population.

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door!

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door!Ideally, the guidelines will allow adults with Down syndrome to receive the best possible car e, regardless of where they live.

“There are only a few clinics in the entire country serving teens and adults with Down syndrome,” Dr. McGuire said. “So there are huge numbers of them without access to specialty care. They go to local doctors, who may see just a few people with Down syndrome over the course of a year. The guidelines can provide those physicians with a resource they can tr ust, which will help them deliver better care.”

ADDRESSING KEY AREAS OF MEDICINE

Initially, the new guidelines will cover medical car e across multiple disciplines, including cardiology, immunology, behavioral and mental health, and obesity/metabolism.

“We want to eventually cover many more areas,” said Michelle Sie Whitten, President and CEO of Global. “Unfortunately, Down syndrome is still one of the least-funded genetic conditions by our federal government. As a result, we won’t have enough evidence-based research to provide definitive guidelines in some areas but will rather be able to make recommendations. However, in identifying the research gaps, we can also prioritize such research so when we go back to update the guidelines in five years, we have targeted, more comprehensive research to rely on.”

“New health guidelines could prove beneficial for many reasons,” said Dr. McGuire, who worked for 25 years as a behavioral health expert at the Adult Down Syndrome Center at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Chicago. “For example, we’ve found that people with Down syndrome have a tendency toward depression. We also know there’s an overlap between physical and behavioral health. If people have thyroid problems, those can present as behavioral change. When people come in with changes in behavior, behavioral health professionals will recommend a thorough physical exam to make sure there are no physiological issues. If we’re treating depression without treating its physical causes, we’re not really helping [someone with Down syndrome].”

VETTING THE DATA

The first step in the creation of the new guidelines is a rigorous research process by the ECRI Institute, a nonprofit organization that conducts research to create evidence-based medical guidelines. ECRI works closely with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ National Guideline Clearinghouse, which validates the guidelines.

“After that, we’ll gather information from the researchers and clinicians, put it into the form of actual guidelines, and make certain they are published in medical journals,” Dr. McGuire said. “ECRI’s role is to make sure that the quality of this process is extremely high.”

The project has attracted leading medical professionals from throughout the U.S. who provide clinical care to thousands of adult patients with Down syndrome every year. These clinicians will use the ECRI-vetted data as a basis to apply their vast knowledge in different areas and help craft guidelines and recommendations.

The entire process is expected to take two years, and the anticipated completion date is the end of 2018 with the guidelines being available for publication in early 2019.

A VALUABLE RESOURCE

The goal is to have the guidelines published in major medical journals to r each specialty fields and as many medical professionals as possible. The guidelines will be free to parents, caregivers, healthcare providers, and local Down syndrome organizations.

“Parents have always been, by far, the best advocates for people with Down syndrome,” Dr. McGuire said. “We’ve made certain to have a version available to families so they can use them to advocate for their sons and daughters .”

WORTH THE COST

The two-year-long process of creating the new Medical Care Guidelines for Adults with Down Syndrome is costly. Global Down Syndrome Foundation has committed to funding this important initiative, translating the guidelines into 10 languages, and updating them every five years. Global is reaching out to the Down syndrome community for donations, and so far, 28 Down syndrome organizations and multiple individuals have contributed. Their generosity will be recognized in the published guidelines.

“Research is expensive,” said Dennis McGuire, Ph.D., LCSW, Senior Consultant at Global. “Many groups have already stepped up to help fund the guidelines. They know how important this is and are very excited.”

Your ongoing support is crucial to ensuring the best-quality guidelines. To donate, visit

www.globaldownsyndrome.org/donate/

“Tens of thousands of people with Down syndrome reach adulthood each year, and this increases the importance of and need for evidence-based guidelines in this expanding group. Recommendations applied to a person with Down syndrome as a child may not be relevant in adulthood,” said Kent McKelvey, M.D., who leads the Adult Medical Genetics and Down Syndrome Clinic at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. “The presence of three copies of chromosome 21 has implications for development and aging in every organ system. This seems logical and we have some understanding of the processes on a molecular level. We see patterns of disease predisposition with age but we have not translated this into a comprehensive medical management approach. A systematic process such as this is needed to find the gaps in the evidence and order the current evidence into usable guidelines for primary care doctors.”

Like this article? Join Global Down Syndrome Foundation’s Membership program today to receive 4 issues of the quarterly award-winning publication, plus access to 4 seasonal educational Webinar Series, and eligibility to apply for Global’s Employment and Educational Grants.

Register today at downsyndromeworld.org!

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant!

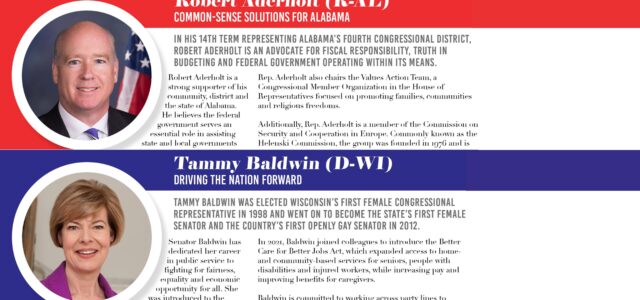

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant! Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.

Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.